by Sylvia Barbara Soberton

Sylvia is stopping by today in celebration of her new book, The Forgotten Years of Anne Boleyn: The Habsburg and Valois Courts. Enjoy the excerpt below. Click on the book cover image at the bottom of this post to order Sylvia’s book. –Heather

Anne Boleyn’s taste in music

Anne Boleyn spent her formative years between 1514 and 1521 at the French court. She first served in the household of Mary Tudor, Henry VIII’s younger sister, and then Claude of Valois, wife of the new French King François I.

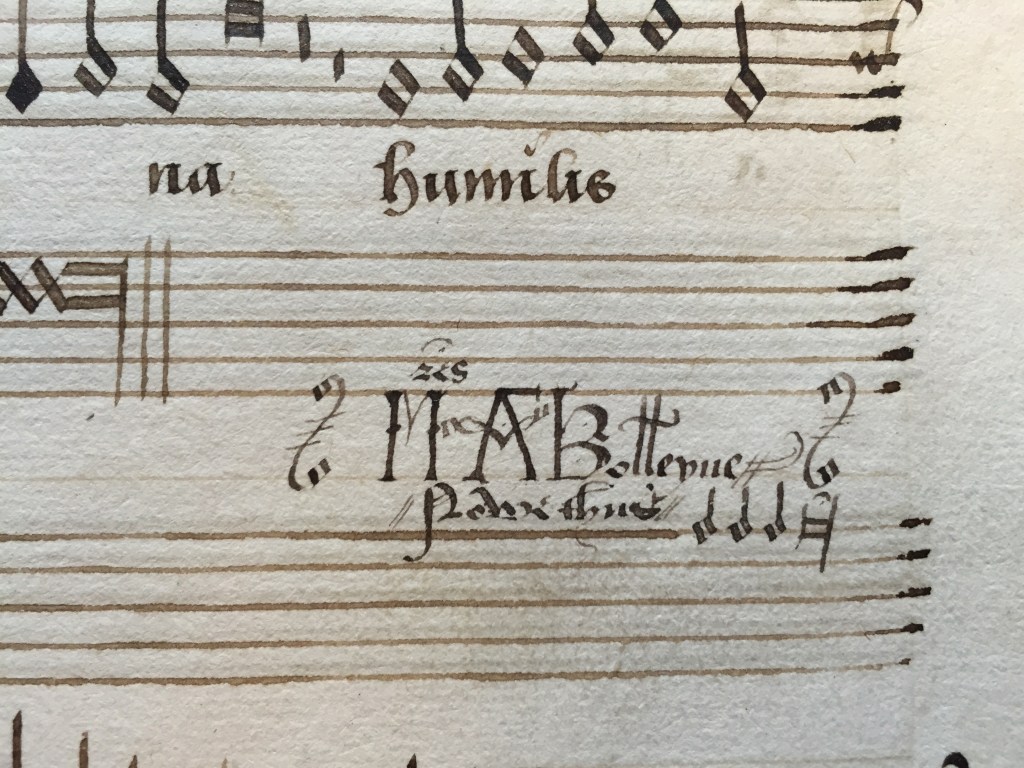

Before Anne left France in late 1521, she received a music book from Marguerite of Alençon, the French King’s sister. This valuable manuscript, comprised mainly of Franco-Flemish motets, can be firmly linked to Anne because she signed her name there: “Mris [mistress] A Bolleyne / Nowe thus”, followed by a musical motto of three minims and a longa.[1] For many years, it’s been erroneously assumed that the manuscript was created for Anne and presented during her years as Queen of England, probably by Mark Smeaton, musician of her Privy Chamber. The research conducted by Dr Lisa Urkevich, however, corrected this long-held view. Urkevich argued that the manuscript dates to the early sixteenth century and is of French origin.[2]

It remains unknown for whom it was originally created or how many owners possessed it, but one thing remains clear: Anne must have first owned the manuscript when she was young. This is attested by the signature. She signed herself as “mistress” and attached her surname Boleyn to it, together with her father’s motto, “nowe thus”. This proves that Anne must have been indeed young, still only a “mistress”, without fame or distinction, and not a marchioness (she was elevated to peerage in 1532) or queen (crowned in 1533). Throughout her life, Anne signed her letters as “Anne Boleyn” (before her ennoblement), “Anne Rochford” (from 1529) and “Anne the Queen” (from 1533). It’s been credibly suggested that Marguerite gave the manuscript to Anne when she learned of Anne’s impending marriage to James Butler—this would explain why Anne signed her name under a song about marriage (Loyset Compère’s Paranymphus salutat virginem).[3]

It’s also interesting to note that Anne placed her signature beneath the alto part, which may have been the part she sang. People who knew Anne widely commented upon her musical talents, saying that she was skilled “in playing on instruments, singing and such other courtly graces, as few women were of her time”.[4] Later in her life she owned a pair of clavichords that she decorated with green ribbon and it was said she “knew perfectly how to sing and dance . . . to play the lute and other instruments”.[5] However, the often quoted passage from Agnes Strickland’s nineteenth-century biography of Anne, where Anne was said to have sung “like a second Orpheus” is a myth. The whole passage reads:

“She [Anne Boleyn] possessed a great talent for poetry, and when she sung, like a second Orpheus, she would have made bears and wolves attentive. She likewise danced the English dances, leaping and jumping with infinite grace and agility. Moreover, she invented many new figures and steps, which are yet known by her name, or by those of the gallant partners with whom she danced them. She was well skilled in all games fashionable at courts. Besides singing like a siren, accompanying herself on the lute, she harped better than King David, and handled cleverly both flute and rebec. She dressed with marvellous taste, and devised new modes, which were followed by the fairest ladies of the French court; but none wore them with her gracefulness, in which she rivalled Venus.”[6]

This passage is still quoted as factual by Anne’s biographers although the nineteenth-century historian John Lingard discovered that it was part of a never published historical novel.

Anne’s music book contains 39 motets (two without texts) and three French secular pieces. It is a rare survivor of Anne’s early years and provides a link to her time at the French court. In 2015, a recording entitled Anne Boleyn’s Songbook, was released by the early music ensemble Alamire, allowing us to reconnect with Anne five centuries later, listening to the same music she would have been familiar with.

[1] MS 1070 (Anne Boleyn Music book), Royal College of Music, London.

[2] Lisa Urkevich, “Anne Boleyn, a music book, and the northern Renaissance courts: Music Manuscript 1070 of the Royal College of Music, London.” PhD dissertation, University of Maryland, 1997.

[3] Lisa Urkevich, Anne Boleyn’s French Motet Book, a Childhood Gift, pp. 95-119.

[4] William Thomas, The Pilgrim: A Dialogue, p. 56.

[5] Susan Walters Schmid, Anne Boleyn, Lancelot de Carle, and the Uses of Documentary Evidence, p. 112.

[6] Agnes Strickland, Elisabeth Strickland, Lives of the Queens of England, Volume 2, pp. 571, 572.

You Might also Like: Anne Boleyn’s Coronation The Curious Case of a Misidentified Portrait of Anne Boleyn Anne Boleyn: The Difference of 1,100 Days Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII: The Last Love Letter