by Heather R. Darsie

On 13 June 1525, forty-one-year-old Martin Luther married twenty-six-year old Katharina von Bora. Katharina was given to the Church at a young age. By her early twenties, she and several other nuns in the Marienthron convent were familiar with Luther’s teachings and wished to practice them. They became fed up with religious life, and wanted to leave the convent.

Katharina von Bora c. 1526 by Lucas Cranach the Elder, via Wikimedia Commons.

The convent of Marienthron was in anti-Reformation ducal Saxony. In a time of rampant closure of religious houses in electoral Saxony, the Marienthron in ducal Saxony did not close until at least the late 1530s. However, despite her vows, Katharina was ready to leave.

Katharina and eleven or so of her fellow rebel nuns contacted Martin Luther in pro-Reformation electoral Saxony, asking him to help them escape. The day before Easter 1523, Katharina and her friends escaped in a herring cart driven by a friend of Luther’s. They were taken to Wittenberg. The arrival of the nuns on 7 April 1523 was described as, “A wagon load of vestal virgins has just come to town, all the more eager for marriage than for life. God grant them husbands lest worse befall.” Luther published a booklet in late April about the event, admitting his role in the escape, and exhorting others to likewise escape from religious houses.

Clerical Marriages in Germany Before the Reformation

Leading up to the German Reformation, priests were not allowed to marry. Concubinage was a common practice in Germany amongst priests. Clerical concubinage was widely, if begrudgingly, accepted during the medieval period and into the early modern sixteenth century in Germany. Luther felt outraged by the practice of concubinage. On the other hand, Luther was uncomfortable with the idea of marrying at first. One of his loudest students-turned-Reformers, Philippus Melanchthon, was initially firmly against it. This made Melanchthon a bit of a hypocrite because he himself wound up marrying in November 1520.

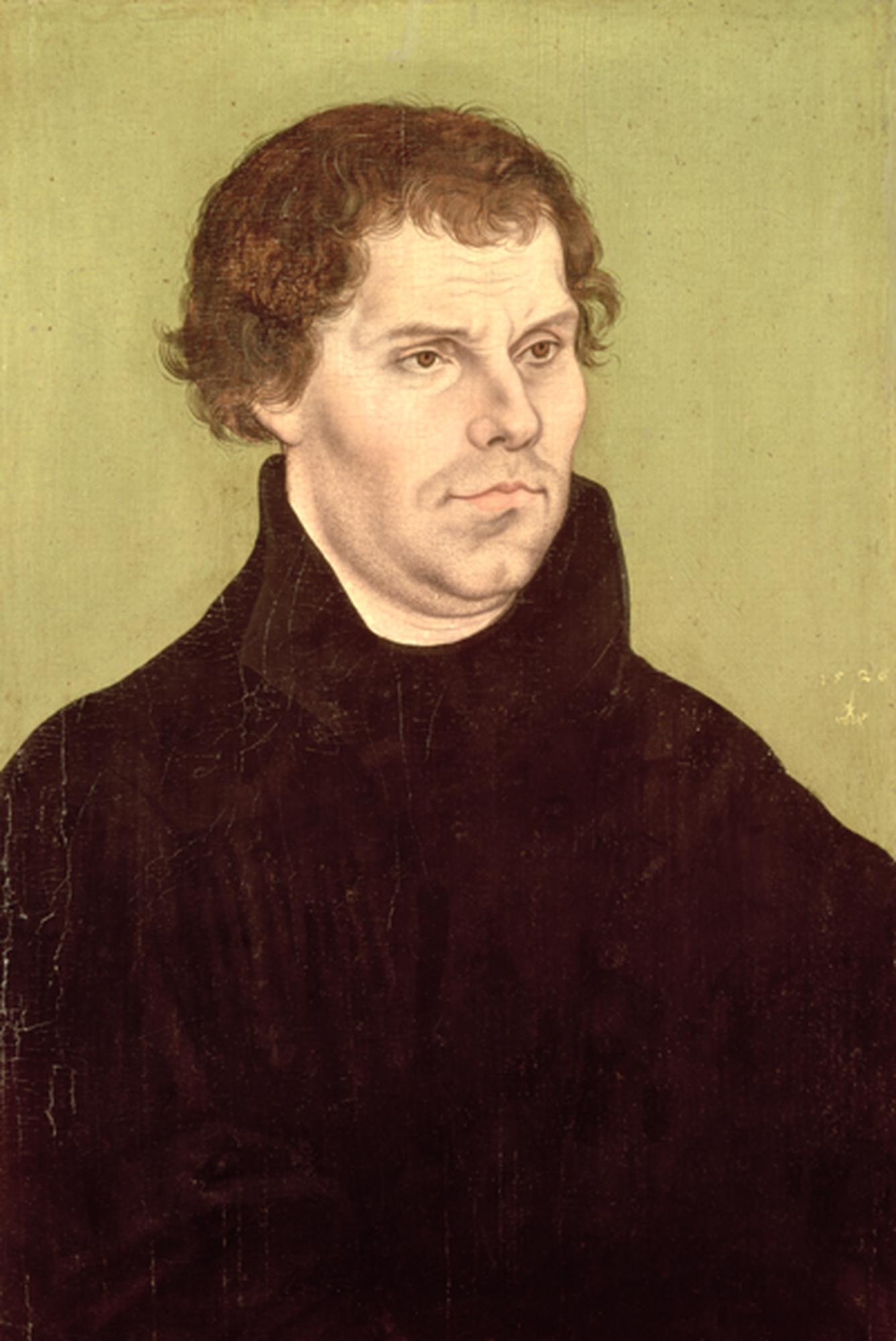

Martin Luther c. 1526 by Lucas Cranach the Elder, via Wikimedia Commons.

Once the Reformation began, it took a little bit of time before the main proponents of the Reformation, including Luther, accepted clerical marriage. Luther did not accept clerical marriage until he married Katharina von Bora. With the closure of abbeys and convents, families who previously gave up their daughters to God now had extra mouths to feed and dowries to provide. Having the extra mouth to feed, in a time of predominantly non-commercialized farming in Germany, was a serious burden and potential danger to the survival of a family. The solution was to wed former nuns to former monks, who did not require much, if any, dowry.

Negative opinions on the sanctity of marriages between persons religious were bolstered by pamphlets. The pamphlets stated things such as married persons religious were akin to knaves and whores. Additionally, former persons religious were sometimes regarded as having committed adultery against God, or of being incestuous by wedding their spiritual brother or sister.

Clerical Wives

Major threats to women marrying former monks and current religious leaders existed from 1521 to 1534. Women, and not necessarily even former nuns, violated canon and imperial law, not to mention local. They were deemed a “priest’s whore”, and commonly faced economic hardship. Marrying a former cleric was a serious social dishonor for a woman.

Despite these serious social issues, marriage was at times the best solution for women released back into society to avoid additional burdens on the family. The extra burden was a concern faced by members of the nobility too. Protestant families experienced a surge in marriages because that was the more economical choice for returned daughters who were now free to marry. The Reformation, a decidedly theological movement, brought a strong element of being a social movement.

Luther’s Stance

Luther gave his official opinion on clerical marriages in 1520. Luther determined that celibacy was not necessary, because marriage was a civil affair. However, Luther reasoned, marrying was safer for one’s soul in that it avoided other sexual sins and thus better protected the spirit. He advocated that individuals had the choice to marry or not. Luther believed that a vow of celibacy was a, “devilish tyranny”, therefore it was better for priests and religious persons to marry to avoid sin. He did not take an official position on whether it was better for an individual to marry or remain single. Luther also held that vows of chastity were not genuine until a person reached a certain age, somewhat akin to the idea that marriage negotiations could be undone if the bride or groom were under a certain age. Luther himself declared in late 1524 that he had no intention of ever marrying. Katharina had other plans.

The Marriage and Reactions

The decision to wed on 13 June 1525 went by unannounced. It was a small affair in the Wittenberg parish church. The famous painter Lucas Cranach and his wife witnessed the marriage. In some circles, Katharina von Bora’s and Martin Luther’s marriage was considered spiritually incestuous. The consummation of Katharina’s marriage to Martin, witnessed by at least one observer, was a flagrant defiance of incest. After all, the couple originally took irreversible holy vows and followed holy orders. That made them brother and sister in Christ. Additionally, by marrying and consummating the marriage, Katharina and Martin committed heresy with their bodies. They were also considered adulturers for abandoning Christ, to whom they were both spiritually betrothed.

The belief was that Katharina and her new husband would burn in hell. Any baby they conceived would be hideously deformed and end in miscarriage. Should a baby of theirs survive the pregnancy and birth, then surely it would be the Antichrist. Of course this was rubbish, and the couple went on to have six well-formed children together.

Love learning about the Reformation or Early Modern period? Are you interested in Tudor history or Women’s history? Then check out my book, Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’, a new biography about Anna of Cleves told from the German perspective!

Please check out my new podcast, Tudor Speeches.

You Might Also Like

- Katharina von Bora

- 16th Century Religious Reformation: What Did the Term “Reform” Mean?

- Martin Luther’s Influence on the German Language

- The First Cracks in Anna of Cleves’ Marriage to Henry VIII

- Poor Relief in Reformation England, Germany, and the Netherlands

Sources & Suggested Reading

- Plummer, Marjorie E. From Priest’s Whore to Pastor’s Wife: Clerical Marriage and the Process of Reform in the Early German Reformation. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing (2012).

- Fudge, Thomas A. “Incest and Lust in Luther’s Marriage: Theology and Morality in Reformation Polemics.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 34, no. 2 (2003): 319-45. Accessed June 12, 2020. doi:10.2307/20061412.

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry. Convents Confront the Reformation: Catholic and Protestant Nuns in Germany. Vol. 1. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press (1996).

- Scribner, R. W. Religion and Culture in Germany (1400-1800). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV (2001).

3 thoughts on “The Scandalous Marriage of Katharina von Bora and Martin Luther”