by Heather R. Darsie, J.D.

The sixteenth century saw massive changes in the spiritual and visual culture of Western Europe. In the first half the sixteenth century, government-sanctioned iconoclasms during the German and English Reformations changed not only how people worshipped, but also what they saw. In the second half of the sixteenth century, religious revolts in France and the Netherlands violently changed the religious landscape of both areas.

This essay follows the slow spread of iconoclasm, beginning in Lutheran Wittenberg, going into Switzerland, then England, and finally back to Paris and the Netherlands. This essay is organized this way because it presents a timeline from the early 16th century to the late 16th century. This organization will show the motivational factors of iconoclasm across geographical regions, along with similarities regardless of distance between political bodies.

Germany and Switzerland, 1518 to 1524

In Wittenberg, Germany, starting around 1518, an iconoclasm was instituted by Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt. The destruction caused by Karlstadt when he stood in for Martin Luther during Luther’s absence from Wittenberg in 1518 to 1522 was rapid and astonishing.

A painting of St. Luke by Jan Gossaert was a reaction to protestant iconoclasm in Germany and Switzerland. The painting is similar works produced by Gossaert in the 1520s to pinpoint the year in which the painting was executed. Gossaert’s painting of St. Luke is a response to the progression of the Lutheran movement in Wittenberg.

Karlstadt began his iconoclasm in late 1521. Particularly, “In December 1521, images were removed from Wittenberg churches, and a number were destroyed.” Following up on this course of action, Karlstadt published a tract in early 1522 justifying the destruction of images.

Opponents of the iconoclasm, and also of Martin Luther, “wrote in Latin, suggesting that the ideas to be refuted were not limited to Germany, but had spread across Europe.” After the Diet of Worms in 1521, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V faced threats of iconoclasm elsewhere in his domains. The artist Gossaert created in 1522 a painting of Saint Luke Painting the Virgin, with allusions to the burgeoning iconoclasm within the Holy Roman Empire.

An ordinance from Wittenberg, two tracts published by Karlstadt, and Karlstadt’s sermons, published between late 1521 and early 1522, show that in Luther’s absence, Karlstadt was ramping up his arguments for iconoclasm. Karlstadt effectively used his sermons and an ordinance from January 1522 to organize the removal of altars and saints’ images from local churches. Luther was not in favor of these changes.

Karlstadt was fairly ruthless is in executing his vision of Luther’s teachings. Whilst Luther was away, Karlstadt published the aforementioned 1522 tract. A year before the tract of 1522 was published, Karlstadt supported the 24 January 1521 ordinance. The ordinance was, „One provocative element of that ordinance, to which Luther took strong exception in the Invocavit Sermons of 9-16 March, was the planned removal of the altars and images of the saints.”

Karlstadt felt that Wittenberg, and the Reformation, were undergoing a crisis. Karlstadt had doctorates in theology, civil, and canon law. Karlstadt used the Old Testament as a type of administrative code, and based his beliefs and writings concerning images upon the Old Testament. These beliefs put Karlstadt at odds with Luther. Karlstadt’s, “prophetic rhetoric calling upon the church to remove images…inextricably describes a “true Christian” differently than Luther’s does.” Karlstadt believed strongly in brand of reform, believing that iconoclasm was necessary in order to stop offending God.

Most importantly, Karlstadt’s On the Removal of Images, “is virtually the first significant discussion of iconoclasm in the Reformation.” Karlstadt’s writings, meant for lay, and not just clerical or royal consumption, pointed out the Old Testament’s stance on graven images, and, “applies them to contemporary abuses in churches and monasteries.” Additionally, Karlstadt approaches his three-prong argument as a prosecutor would. This could be in part because the pamphlets were created for consumption by the masses, although the contents were couched in theological language.

In summation, Karlstadt used a variety of methods to communicate the need for iconoclasm. Karlstadt’s tactic of communicating directly with the laity ensured a larger degree of success in the removal of images. Unfortunately for Karlstadt, his rhetoric conflicted too greatly with Luther’s for Karlstadt to make much progress.

The iconoclasm started by Karlstadt under Luther’s watch spread to Switzerland, with Leo Prud preaching against images. The idea of iconoclasm was bolstered by the preaching of Huldrych Zwingli.

The violence against images in Zurich spread to the Swiss countryside, including the Thurgau. One of the more striking events of the rural iconoclasm in the Thurgau region of Switzerland was the destruction of a statue of St. Anna. The statue was considered ancient even in the 16th century, and so fragile that it was feared attempts at restoration would further damage or destroy the statue. The statue of St. Anna was popular with pilgrims, and thus helped the surrounding area economically through the religious tourism industry. Destruction of the statue shows how the peasantry was disgruntled by the expanding wealth and landownership of the church.

The rural iconoclasm,

“…following the Bildermandat thus went further than just testing the power of the Catholic hierarchy by humiliating the idols… it signaled the adoption of a new order in the most powerful way possible. By openly destroying the most venerated image in the region [the statue of St. Anna], the Thurgau community leaders rejected the old order and asserted their independence of the rules of the Catholic church.”

As will be reflected upon later, iconoclasm sometimes had a political, rather than purely religious, motivation.

England and the Tudors, c. 1525 to 1603

Moving to the western edge of Europe, the English engaged in a unique set of activities as part of the local iconoclasm, which spanned both the 16th century Reformation and the English civil war of the mid-17th century. Although not unique to England, the disfigurement of statues, paintings, etc., was a common form of iconoclasm. Several statues and paintings, instead of being utterly destroyed, had the noses and hands stricken off for the former, or had the faces and hands scratched or otherwise marred for the latter. Evidence of iconoclastic destruction from the reigns of Henry VIII (1509-1547), Edward VI (1547-1553), Mary I (1553-1558), and Elizabeth I (1558-1603) exist.

The act of destroying just the nose or face and the hands of religious icons is peculiar to English iconoclasm. On the Continent, iconoclasm was more an act of obliteration than the English mode of disfigurement.

In some cases, the disfigurement of a single display of religiosity occurred over two centuries. Archaeological evidence found at Lincoln Cathedral and St. Paul In-the-Bail, both in Lincoln, Lincolnshire County, England. The shrine of St. Hugh inside Lincoln Cathedral suffered its first disfigurement at around the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII’s reign, with the face of a statue being chipped away and then smoothed. Over a hundred years later, the very same statue was completely decapitated, then tossed in a well at nearby St. Paul’s.

Henry VIII’s iconoclasm from the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the 1530s and 1540s was relatively mild compared to the ferocity of his son Edward VI’s truncated iconoclasm, begun in 1547. During Edward’s reign from 1547 to 1553, it was specifically decreed in 1549 that the citizenry of England should, “deface and destroy or cause to be defaced and destroyed” icons, images, and the like.

Iconoclasm in England took place as early as 1522. An instance of iconoclasm at St. Mary’s Rickmansworth, to the northwest of London, tells of arsonists who burned the front of the church, and set fire to statues within the church, causing extensive damage. The arsonists were never found. It is suspected that the arsonists were Lollards, a religious movement founded in the mid-14th century who were effectively proto-Protestants.

The politics of image destruction and stances taken by various religious groups such as the Lollards in the 14th century and official policy implemented by Henry VIII because of his break from Rome are important to consider. The Reformation iconoclasm gave part of the push toward secularization of art, “the medieval image of Christ and his saints was inextricably bound up in a whole philosophical fabric of political and social order,” and that, “an inner iconoclasm, or the theological rejection of images, was part of medieval thinking.” This “inner iconoclasm,” or at least concerns over idolatry during the Reformation, may have been a way for Henry VIII’s and Edward VI’s reforms to take hold.

Overall, the destruction of any religious, Catholic imagery that filled English parish churches was completed during the reign of Edward VI, in stark contrast to the reign of Henry VIII. Specifically, “the shift in religious culture from visual to verbal presentation of divine mysteries is one of the most pressing issues on the agenda of English Reformation historiography.” Over the space of roughly forty years, between 1535 and 1575, religious imagery was removed from English churches and replaced with the royal coat of arms, and perhaps a copy of the Ten Commandments. Unfortunately, “we know nothing of what it was like to experience the process [of the destruction of imagery in parish churches], whether as active iconoclasts or iconophiles.”

The roots of iconoclasm in England can be traced back to the Lollards, who were led by John Wycliffe in the 14th century. Later, the burgeoning Protestant movement clung to the Lollard idea of iconography being in fact idolatry, and wished to remove all idolatry from worship. A serious distinction made between the German and English iconoclasms is that whereas the Germans in some instances rioted and mass-destroyed images and items, the images and items in English churches were usually removed through the employ of carpenters and other skilled individuals paid by churchwardens to effect Henry’s and Edward’s royal decrees.

Unexpected sources of information about iconoclastic thinking in 16th century England and greater Europe include Sidney’s poetry and Elizabeth I’s laws. Iconoclasm was an ongoing struggle during the reign of Elizabeth I of England, who reigned from 1558 to 1603.

The foundation of iconoclasm can be summed up as,

“At the heart of Reformation iconophobia was the second commandment’s warning against the worship of any “graven im- age,” and it was religious statuary whose aesthetic appeal inspired the greatest fear. Statues of the Virgin Mary and the saints were often painted, plated with gold and silver, and encrusted with jewels. The statue’s three-dimensionality also heightened its eroticism. Desiderius Erasmus had complained of Catholics kissing and fondling statues that became synonymous with the alluring but corrupting whore. Moreover, since scripture had defined idolatry as a kind of spiritual fornication, idols were by definition whores: “as the looking upon an harlot will infect one with bodily uncleaness, so also the looking upon an Idol will pollute an ignorant and blind heart with Idolatry, and bring it to confusion.”

The Elizabethan iconoclasm was particularly violent, during which, “statues were burnt, smashed”. In addition,

“In London, in 1559, two huge bonfires were made of crosses, Mass books, and paintings but also of ‘Maries and Johns and other images,’ and this process was repeated by the royal visitors throughout England and Wales in that year, and remained official policy to the end of Elizabeth’s reign.”

Specific Elizabethan Acts of Parliament led to the intense iconoclasm of 1559 and the following years. Namely,

“Not only the Visitation Articles of 1559 but also the Injunctions, which remained in force until the end of Elizabeth’s reign, demanded of the clergy that they “shall take away, utterly extinct and destroy all shrines, covering of shrines, all tables, candlesticks, trindals, and rolls of wax, pictures, paintings, and all other monuments of feigned miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry, and superstition.”

However, the removal of icons from Elizabethan churches sometimes resulted in pillaged items winding up in the homes of Elizabeth’s subjects. As will be discussed later, this was not a situation unique to England. Elizabeth took action against misappropriated objects by asking her clergy,

“whether you know any that keep in their houses undefaced any images, tables, pictures, paintings, or other monuments of feigned and false miracles, pilgrimages, idolatry and superstition, and do adore them, and specially such as have been set up in churches, chapels, or oratories.”

Through trying to show the religious themes in Sidney’s work, a surprising amount about Elizabethan iconoclasm early in Elizabeth I’s reign can be gleaned.

In some ways, iconoclasm could be interpreted as being anti-women. There was a line of thought in the 16th century that extended from Germany to England, proposing that images of female saints were whorish, thereby justifying the destruction in which Reformed Catholics and Protestants engaged. Specifically,

“Reformers…associate the devotional gaze with the erotic gaze, and they liken sacred images to the sexualized woman who, although beautiful, is dangerously seductive. Many of these images were of course idealized representations of holy women, and are especially singled out. Protestant polemics rage against representations of the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the female saints because, they assert, these images portray the female body in such a way as to arouse carnal desire.”

This reaction to images in Elizabethan England is similar to Karlstadt’s feelings in Wittenberg decades earlier. In Reformation Germany, in paraphrase of Desiderius Erasmus,

“Distressed by what they perceive to be a pervasive, indeed, almost universal, iconophilia among the devout, Protestant reformers and reform-minded Roman Catholics alike express concern because so many lay worship- pers treat images as if they were alive; that people should bow their heads, fall on the ground, or crawl on their knees before them; and that worshippers should kiss or fondle the carvings.”

If this was indeed what was happening at times with statues and carvings, perhaps the movement toward iconoclasm in the earlier decades of the Reformation make a bit more sense to the modern observer.

In some instances, iconoclasm in England was justified by civic authorities as a way to bring morality and remove sexual temptation from the community. In short, by removing “bewhored” idols, things like prostitution would likewise decrease in the community. By removing images, the civic authorities prevented “spiritual whoredom of the heart”. Effectively, iconoclasm was not a senseless act of violence by Reformist or Protestant actors, but rather an effort to remove temptation and perversity from religious spaces.

However, in contrast to Elizabethan England, “iconoclasts almost never looted the images for material gain, instead preferring to deface or desecrate them in certain highly symbolic ways, gouging out their eyes or piercing their sides. Indeed… the iconoclasts seem to engage in a symbolic kind of killing: they decapitate, dismember, torture, disfigure, and even crucify these images.” While this does support the archaeological investigation of iconoclasm in England, it is potentially conflicting with what was experienced in Elizabethan England. The Elizabethan decrees were enacted specifically because of a concern that items of worship were being used in private home chapel settings.

The Habsburg Netherlands, 1566 To 1585

Shifting back to continental Europe, it is important to gain insight into what motivated iconoclastic behavior, some of which parallels the motivations of the Swiss. The first “iconoclastic riots” occurred in 1566 in the Westerkwartier, “an area rife with Calvinist agitation….” Specifically, the riots started with a man attacking a little chapel by Steenvoorde. The chapel was dedicated to St. Lawrence, and was attacked on his feast day of 10 August by a Calvinist preacher and some of his followers. After preaching a sermon, the group entered the church and destroyed whatever paintings and statues of religious figures they could find. Generally, “vernacular denunciations of Catholic image worship in the forms of treatises or plays were plentiful.” Thus, the idea of religious imagery being popish, violative of the second commandment, and decidedly pro-Catholic and pro-Spanish, were widely known in the area.

The Netherlands iconoclasm was much more thorough in its destruction than those in Germany, England, or Switzerland. Specifically,

“the whole material accoutrements of the church, from clerical vestments to liturgical books and baptismal fonts, had become targets as the attackers sought to cleanse and purify interior spaces crowded with a dense variety of sacred objects.”

This is in contrast to the initial attempts by Karlstadt to remove only images, the destruction of the St. Anna statue in Switzerland, and the gradual Dissolution of the Monasteries in England. The way in which the iconoclasm was carried out is much different than iconoclastic manifestations in other parts of Europe.

The iconoclasm of 1566 in the Netherlands was carried out by an organized group of religious rioters. Specifically, “From the accounts of witnesses and trial records of captured iconoclasts, it is clear that the riots were…a series of coordinated attacks led by a band of iconoclasts under the leadership of preachers…” This differs from the government-sanctioned iconoclasm in England and the iconoclasm in rural Switzerland, although there are heavy echoes of the iconoclastic activities in Karlstadt’s Wittenberg and in Zwingli’s Zurich.

Trial court records from the time period show who comprised the group of iconoclasts. Although the sample size of iconoclasts is not ideal, one can determine the profession of the bulk of the iconoclasts. Several worked in a capacity related to draperies, multiple artisans, such as, “a chairmaker …clothmakers, a shoemaker, …innkeepers…” and so on. Lastly, there were a few civil servants accused of iconoclasm. Professions related to draperies were swiftly losing their earning capacity due to poor trade agreements between the Spanish King Philip II, who was the hereditary overlord of the Burgundian Circle, and England, who produced much of the wool used in the Netherlands. The economic composition of the iconoclasts echoes that documented in Paris and in rural Switzerland, in that the bulk of the individuals had somehow in truth or in feeling seen their livelihoods be impacted by action of the government, which during the Early Modern period was closely tied with behavior of the church.

Iconoclastic acts in the Netherlands did not stop there. There was an enduring spread of iconoclasm throughout the Netherlands:

“In 1572 and 1573 the rebel armies in Holland and Zeeland killed priests, plundered convents and mocked the sacraments; church prop- erty was requisitioned, and from 1573 Catholic worship was outlawed there. Between 1577 and 1585 Calvinists in Antwerp, Ghent, Bruges, Ypres and Brussels disturbed processions, burned books, broke images, expelled priests and eventually banned Catholic worship altogether.”

In contrast to their French counterparts, who were summarily slaughtered and mutilated in the streets, Pollman asserts that, “Catholic lay people in the Netherlands were almost completely passive in their response to Reformed activism.” The early French Wars of Religion were somewhat contemporaneous with the Dutch iconoclasm.

A different perspective on causes for conflict between Huguenots and Catholics living in Paris leading up to and during the French Wars of Religion starts with activities in France in the 1560s, rather than reviewing the catalyst of events such as the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre in 1572 solely from a political perspective. Religious violence in Paris became serious as early as 1561, four decades after strict anti-Reformation preaching became the norm. Catholicism, deeply intertwined with the monarchy, had to be maintained at all costs. Even if those costs were violent.

The main difference between French human brutality and Netherlandish object brutality was who tried to enforce concepts of toleration. In France, after the accidental death of Henry II in 1559 and his son Francis II in 1560, the monarchy was unstable and in the hands of Catherine de’Medici. She, through her young son Charles IX, tried to legislate toleration between Catholics and Calvinists. The Catholics were unimpressed.

In the Netherlands, it was the citizenry who wanted toleration. King Philip II and his father Charles V were very much in the habit of hunting down and destroying heretics. By the 1560s, a large group of lesser nobles were able to convince (or, perhaps, gently coerce) Philip II’s Regent of the Netherlands, Margaret of Parma, to capitulate to the Dutch nobles’ desire for peace and freedom from persecution, which resulted in Margaret suspending heresy laws. Dutch governmental leaders also had the experience of the violent, radical Anabaptists of 1534-35 from which to draw, and saw, “a clear difference between the seditious Anabaptists and respectable dissenters, who counted many a bourgeois amongst them.” On top of that, enforcement of anti-heresy laws in the Netherlands had more-or-less dropped off by the end of the 1550s.

Thus, many of the iconoclasts who acted in August 1566 believed they were acting on behalf of the local nobility. For a time after the August iconoclasm, the idea of religious peace spread throughout most of the Netherlandish provinces. Unfortunately, the peace was not to last, and Philip II swiftly took action to oust the heretics.

Conclusion

The motivation behind iconoclasm varied greatly region to region and decade by decade during the 16th century German and English Reformations. Religious reform, naturally, was the partial motivation of the iconoclasms discussed in German Wittenberg, Swiss Thurgau, Tudor England, and the Spanish Netherlands. However, the minor details all differ. In Wittenberg, Karlstadt thought that all religious images were offensive, whereas Martin Luther only thought some were, depending on context. In the Thurgau, iconoclasm was likely influenced by previous iconoclastic activities in Zurich, but was mostly motivated by the increasing poverty of the peasantry when compared to the increasing wealth of the local church. In Tudor England, the motivation of iconoclasm changed from monarch to monarch, and in some instances carried on into the mid-17th century. Iconoclasts in the Spanish Netherlands thought they were being good subjects to the local nobility by tearing down and destroying religious imagery. Whatever the motivation, the only certain thing is that innumerable valuable works of art were defaced or destroyed forever in the 16th century, never to be admired again.

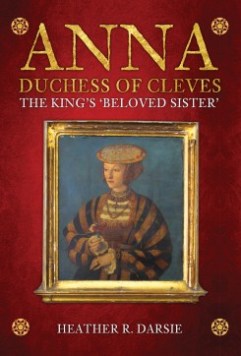

Love learning about the Early Modern period? Are you interested in Tudor history or Women’s history? Then check out my book, Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’, a new biography about Anna of Cleves told from the German perspective!

You Might Also Like

- Poor Relief in Reformation England, Germany, and the Netherlands

- 16th Century Religious Reformation: What Did the Term “Reform” Mean?

- Martin Luther, Henry VIII, and the Papacy

- Henry VIII: How Many Children did He Have?

- When Henry Met Anna: The German Account

Sources & Suggested Reading

- Putting away of Books and Images Act, 3 & 4 Edw. 6 c. 10: 38.

- Arnade, Peter. Beggars, Iconoclasts, and Civic Patriots: The Political Culture of the Dutch Revolt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press (2008).

- Diefendorf, Barbara B. Beneath the Cross Catholics and Huguenots in Sixteenth-Century Paris. New York: Oxford University Press (1991).

- Diehl, Huston. “Bewhored Images and Imagined Whores: Iconophobia and Gynophobia in Stuart Love Tragedies.” English Literary Renaissance 26, no. 1 (1996): 111-37. Accessed October 21, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43447511.

- Graves, C. Pamela. “From an Archaeology of Iconoclasm to an Anthropology of the Body: Images, Punishment, and Personhood in England, 1500–1660.” Current Anthropology 49, no. 1 (2008): 35-60. Accessed October 7, 2020. doi:10.1086/523674.

- Ives, Eric. The Reformation Experience: Living through the Turbulent 16th Century. Oxford: Lion Hudson PLC (2012).

- Kingsley-Smith, Jane. “Cupid, Idolatry, and Iconoclasm in Sidney’s “Arcadia”.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 48, no. 1 (2008): 65-91. Accessed October 18, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071322.

- Leroux, Neil R. “”In the Christian City of Wittenberg”: Karlstadt’s Tract on Images and Begging.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 34, no. 1 (2003): 73-105. Accessed October 10, 2020. doi:10.2307/20061314.

- Maarbjerg, John P. “Iconoclasm in the Thurgau: Two Related Incidents in the Summer of 1524.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 24, no. 3 (1993): 577-93. Accessed October 12, 2020. doi:10.2307/2542110.

- Mcgee, Sears, and Margaret Aston. 1990. “England’s Iconoclasts. Volume 1, Laws against Images.” The American Historical Review 95 (4): 1190.

- Phillips, John. 1973. The Reformation of Images: Destruction of Art in England, 1535-1660. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Pollmann, Judith. “Countering the Reformation in France and the Netherlands: Clerical Leadership and Catholic Violence 1560-1585.” Past & Present, no. 190 (2006): 83-120. Accessed November 4, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3600888.

- Schaefer, Jean Owens. “Gossaert’s Vienna “Saint Luke Painting” as an Early Reply to Protestant Iconoclasts.” Source: Notes in the History of Art 12, no. 1 (1992): 31-37. Accessed October 7, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23207839.

Typo — it should probably be “canon” law, not “cannon” law (though considering the way it was used, “cannon” has a certain charm).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Iconoclasm existed during the fifth and sixth centuries in Byzantium as well and it could get very violent. Many precious early icons were lost. During the wars between Scotland and England in 1639,_the soldiers on their way South not only destroyed what art they could find but tombs and effigies as well.

One benefit of whitewashed walls to cover religious art was that it preserved some of it and a number of churches have made remarkable Medieval finds in good condition when they have removed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person